flowchart TB

start("We want<br>to choose<br>a license.") --"We adapted a work by<br>others shared under a<br>free/open license."--> use_existing_license["<em>Use its license</em>"]

start --"We created the work<br>entirely by ourselves."--> regulation("Other regulation<br>(by community or funder)<br>concerning license?")

regulation --"Exists"--> follow_existing_norms["<em>Follow that</em>"]

regulation --"Does not<br>exist"--> type("Work type?")

type --"Software"--> apache["Apache 2.0"]

type --"Writing, image, audio, video"--> cc0["CC0 1.0"]

type --"Data(base)"--> existing_license_data("Adapting individual<br>data entries by others?")

existing_license_data --"No, we created them<br>entirely by ourselves."--> cc0_data["CC0 1.0 <em>for database<br>and its content</em>"]

existing_license_data --"Yes, they were<br>shared under a<br>free/open license."--> use_existing_license_data["<em>Use their license<br>for content and</em><br>CC0 1.0 <em>for<br>the database</em>"]

click apache href "https://choosealicense.com/licenses/apache-2.0/"

click cc0 href "https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/"

click cc0_data href "https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/"

Choose a License

So far, you took care to legally include works by others in your project folder. Up next, you will free up your project for reuse. This means ensuring that every bit (co-)authored by you in the project is put under a free/open license. It may be that your project (i.e., its files and folders) is not one work, but rather consists of multiple works available under different licenses. In that case, you need to indicate the license on a per-file or per-folder basis (rather than choosing one for the whole project). Sometimes, even different parts of a file might be subject to different licenses. For the purpose of this tutorial, we will consider the manuscript and the bibliography which you edited.

Some journals offer to publish your article under a Creative Commons license, but still demand an exclusive publishing and distribution license or a copyright assignment from you. This would give them more rights than the readers of the article have through the respective Creative Commons license (Rumsey & Labastida, 2022) and exceeds by far what is necessary to make publication possible (Suber, 2022). Consequently, authors should oppose this practice and grant publishers the same rights that every other reader of the article has. To facilitate self-archiving, one can also modify the contract with publishers via a rights retention statement (UK Reproducibility Network & Eglen, 2023) / author’s addendum (SPARC, 2006). If you have published a closed-access paper before, you can consult ShareYourPaper for legal options to still make it available free of charge to readers.

If your chosen publisher insists on an exclusive license, you may at least retain the copyright for your figures – follow the guide “Retaining copyright for figures in academic publications to allow easy citation and reuse” by Elson (2016) to learn how to do that.

We recommend to choose free/open licenses suitable to the type of work (e.g., code, data, image etc.). CC0 1.0 and Apache 2.0 are good choices to apply simultaneously to all own works. Take your time to read the summaries behind the links and/or the actual license text to understand the legal effect. You can adapt the following wording to your use case:

Except where noted otherwise, all files in this project are made available under CC0 1.0 or (at your option) under the terms of the Apache License 2.0.

Which License to Choose for a Work?

Many boilerplate licenses are available to apply to your work. Which license is appropriate depends on several factors, including existing licenses in place and the type of work, but also your personal considerations. We strongly recommend to apply a free/open license to your work that fits to the work type and potential use cases. Because there are many free/open licenses available, the licenses discussed here only represent a recommended subset.

If you would like to choose a license not listed here, it should be appropriate for the type of work in question and be compatible with the dominant copyleft license in the respective community (see also Note 3). For software that’s almost universally the (A)GPLv3 and for writing, image, audio, and video that’s mostly the CC BY-SA 4.0. For databases, no dominant copyleft license has emerged yet, so any of ODbL 1.0, CDLA Sharing 1.0, and CC BY-SA 4.0 are acceptable.

Existing License?

First, if you adapt (i.e., modify, remix, build on) a work by others you need to determine if it is provided to you under a free/open license. If yes, we recommend you to make your contribution available under the same license.1 For example, if you adapt code published in another paper, choose the same license for your modifications. The same applies if there are strong community norms to use a particular free/open license2 or if a particular license choice is mandated by your funder. Importantly, as discussed before, you are generally not allowed to adapt a work not published under a free/open license.

Work Type?

If you create a new work and no strong community norms suggest a particular license, you need to choose the license yourself. Which license to choose depends on the type of work you create. We have created a flowchart that covers the most likely types of works you will create as a researcher: software, writing (i.e., text), images, audio, video, and data (see Figure 1). This flowchart always recommends the most permissive license possible to maximize reuse – though we provide two additional flowcharts below that allow for more choices. Click on the name of a license to learn more about it.

Sometimes, the type of a work is not obvious. For example, a Quarto document…

- …contains both R code and writing, and

- …may be distributed in the source format or as rendered document, possibly including images.

One may wonder which license to apply in this case, because Creative Commons licenses are not recommended for source code3 and applying software licenses to PDFs or images can lead to confusion or nuisance.4

One solution is to make such a work simultaneously available under two (or more) licenses, at the choice of the recipient: Either under a specified software license, or under a Creative Commons license.5 This is called multi-licensing and makes it easier to reuse both the rendered document as well as the code. For example, one could write:

The Quarto documents in this project are made available under CC0 1.0 or (at your option) under the terms of the Apache License 2.0.

We already mentioned that a database may be licensed differently than its content. However, if the content was created by you, we recommend you to choose the same license for both content and database. Factual data (like measurements or metadata) should be made available with CC0 1.0 (Villa, 2016a, 2016b) – otherwise, consult Note 2 for some caveats.

One should take special care when applying license to the following types of works:

- fonts: Copyleft licenses applied to fonts can be a special case: If a font is put under the license CC BY-SA 4.0, any documents containing texts using that font will probably be derivative works and have to be put under the same license if shared. The SIL Open Font License 1.1 is the de facto standard license for fonts, requiring that derived fonts, if published, have to be put under the same license. It doesn’t require attribution for usage (e.g., when embedded in a document), but forbids that the font is sold by itself. Selling the font is allowed, however, if it is bundled with other software.

- templates and TeX packages: If a template or, for this purpose, a \(\TeX\) package, is licensed under a copyleft license such as the (A)GPLv3, every work that is a derivative of it has to be put under the same license if shared. If a document contained source code covered by the (A)GPLv3, it depends on the individual case whether the same license needs to be applied to the document if shared.

- database content: If the work produced from a database (the “output”) is a derivative of the content in the database, the output is subject to the restrictions laid out in the license. For example, if geospatial data were to be licensed under CC BY 4.0, all maps produced from the data would likely need to fulfill this license’s obligation for unrestricted access (its anti-DRM provision) if shared (see Poole, 2017). Similarly, following an example from Matt (2009), if one were to choose the copyleft license CC BY-SA 4.0 for this purpose, any map that is a derivative of the data would also need to be licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 (or a compatible license) if shared. If the intention is to only have derivative databases under the same license, one might want to choose the ODbL 1.0 for the database, as it was specifically designed not to apply to works produced from the data in the database. Otherwise CC0 1.0 is an excellent choice for data.

- works in the public domain: If a work is already in the public domain, it should be marked using the PDM 1.0, rather than applying a waiver such as the CC0 1.0 (or another license).

Copyleft?

You may prefer that adaptations of your work stay free/open and thus choose a copyleft license. Of course, this does not restrict you as the original author: You are still permitted to distribute the work under a different license and without sharing the source code.

In most cases, the output of software, like images or tables, does not depend on the software’s license.6 Therefore, if you use an R package under a copyleft license to create a figure, you are likely the copyright owner. However, if the output is based on data, it can be considered a derivative work of the data and the license of the data also applies. For example, maps may be considered a derivative work of the geographic data they are based on.

It is disputed whether software that uses an R package under AGPLv3 or GPLv37 can only be published under a GPL-compatible license – or even has to be published under the same license. Posit, the company behind RStudio, does not believe that to be the case (see also Wickham & Bryan, 2023).

You can learn which license an installed package uses via packageDescription("<PACKAGE_NAME>", fields = "License"). And to identify which licenses are being used by the R packages your project depends on, you can use the following code:

Console

deps <- renv::dependencies()$Package |>

unique() |>

pak::pkg_deps(dependencies = NA) |>

getElement("package")

unique(installed.packages(fields="License")[deps, "License"])We have prepared two advanced license flowcharts, one for software, writing, images, audio, and video in Figure 2 and one for data in Figure 3 where you can make additional choices. Note, however, that especially the advanced flowchart for licensing data is quite complex and we recommend you to seek legal counsel if you want to be sure.

Additional considerations

The advanced license flowcharts also allow you to make additional decisions, such as whether attribution should be a condition of redistribution. As you have learned, even if attribution is not a condition of the license, there are other reasons for attributing you as an author (such as scientific citation standards or moral rights). All conditions are explained on the page on copyright.

From the Creative Commons licenses, only CC0 1.0 does not require providing attribution, and all software licenses in Figure 2 require providing attribution. As an author, you are free to waive license conditions such as attribution, however.

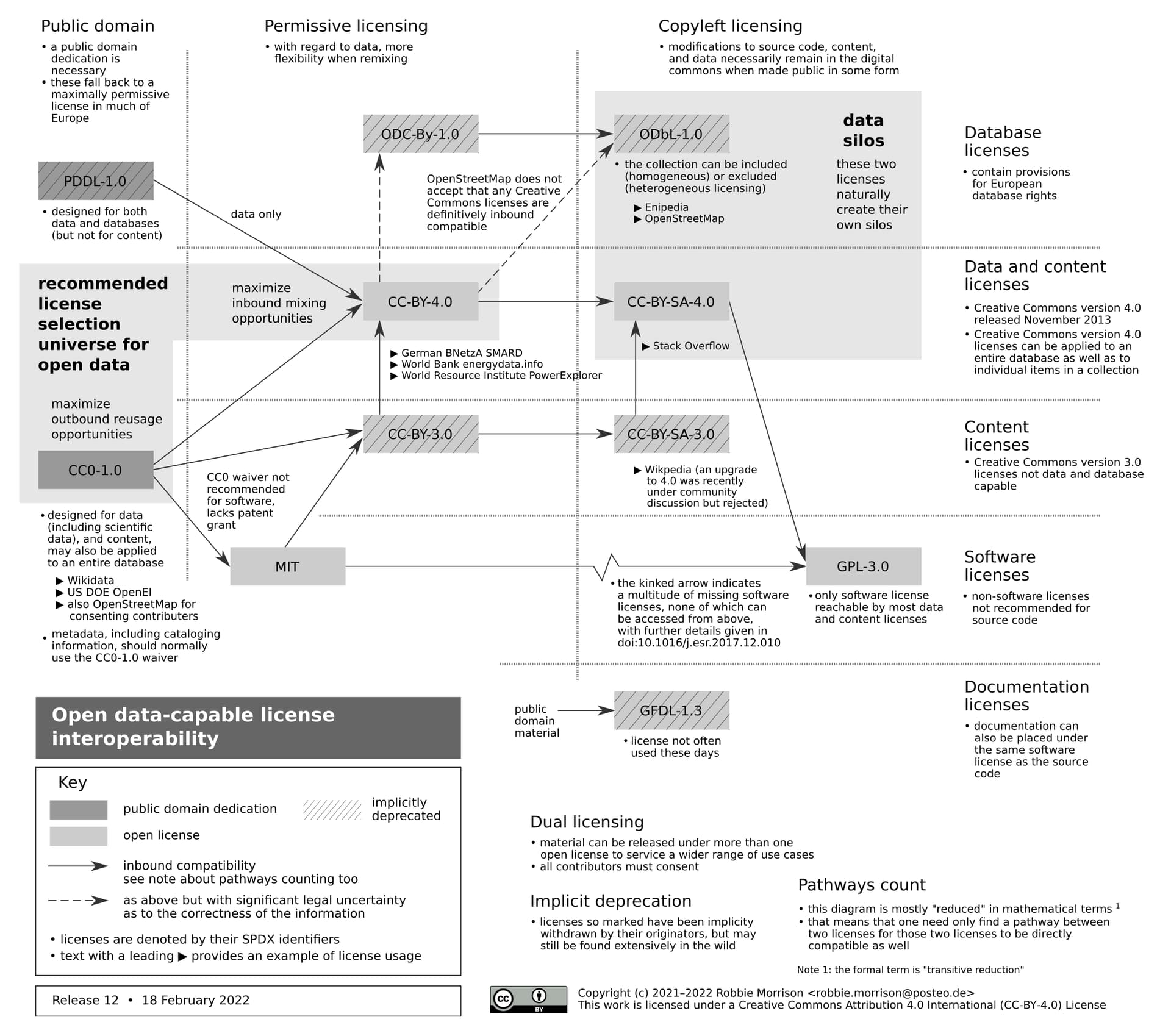

Creative Commons also offers licenses which prevent commercial use of a work and/or sharing of derivative works. A free/open license, however, must allow creating derivative works and must allow exercising the rights granted by it for any purpose, including commercial use. Otherwise, creating adaptations from multiple works by different authors would either limit commercial use for everybody (including the authors) or would not be possible at all (when including materials with a copyleft license), effectively creating silos of works which are mutually incompatible with each other. This is especially relevant for work types for which adaptations are created frequently, such as text, data, and source code. In order to avoid silos, one should only choose licenses which are compatible with the dominant copyleft license in the respective community (Lämmerhirt, 2017; Wheeler, 2014). If you would like to learn more about the different types of compatibility, we recommend you to read the article “A Quick Guide to Software Licensing for the Scientist-Programmer” by Morin et al. (2012). The following diagram provides an overview of the compatibility of various licenses:

Applying the License

Having selected the license(s) of your choice, we encourage you to read through the full license text (or at least a legal summary) to understand the legal effect. The following applies to all licenses mentioned here:

- Applying the license is irrevocable. You may stop distributing your work, but everybody who already received it may continue to share it.

- As an author applying the license, you are not bound by the license terms. You cannot, however, give others an exclusive license to your content anymore (as some journals needlessly demand, see Warning 1).

- By applying the license you share with others your right to use your work for commercial purposes, including selling it.

- If you apply the license to an image, the license may also apply to a higher resolution version of your image.

- If you apply a copyleft license to an image, a document in which the image is used may not constitute a derivative work and, as such, may not be affected by the copyleft condition.

- If you are a member of a collecting society8 or if the work was created as part of your job, you may not be able to apply the license. Check with your collecting society or your employer in that case.

If you are an employee at LMU and your funder does not mandate the use of a particular license, the decision of which license to use lies with the holder of your chair (Lehrstuhlinhaber*in). The only exception is the case that you developed an invention you would like to exploit commercially with a patent. Then, you are required to officially report your invention to the IP management team of the LMU, which will work out the next steps with you.

For Creative Commons licenses, the following is additionally important to know:

- By applying the license you waive any moral, publicity, privacy, or other similar personality rights to the extent necessary to use the work.

- The attribution requirement may be implemented “in any reasonable manner”, possibly not conforming to your precise expectations.

Applying a license to a work mostly just means indicating which file or folder is covered by which license(s) (no sort of registration is required). There are multiple standards on how to do so:

You have already learned about the file

LICENSE.txt. Either it contains the full text of one license that applies to the whole project folder – this is a practice propagated by GitHub, which provides instructions for and comparisons of many licenses via ChooseALicense.com. Alternatively, it details which license applies to what and the individual licenses are stored in the same or in different files.A summary of the licensing situation is often given in a README file, whose creation will be discussed later.

If only parts of a file are covered by a certain license, then it might make sense to indicate this directly in the file.

The license of embedded elements (e.g., images) is either given directly beneath to where they are embedded, at the end of the respective page, or collectively on a separate page.

Individual programming languages also have their own way of stating which license a package is distributed under. For R packages, this is usually set by the field

Licensein the fileDESCRIPTION(Wickham & Bryan, 2023).Software projects often indicate the license in every file, following the REUSE specification to make the choice of license machine-readable (explained in Note 5).

The following two metadata standards for increasing citability also allow to indicate the license:

CodeMeta: All information are stored in a file called

codemeta.json, which can be created on their website. Alternatively, one can use the R packagecodemetarto create this file.Citation File Format (CFF): Here, everything is stored in a file called

CITATION.cff. It is used by GitHub to directly show a recommended citation for a repository. The file can be created on their website. Alternatively, the R packagecffrmay be used for that purpose.

For all the licenses recommended in this tutorial, the organizations that created these licenses provide more information on how to apply them to your work:

Creative Commons even provides a range of considerations for licensors and licensees (Creative Commons, 2013) and an interactive chooser which you can use to create text snippet that you can copy and paste to the desired location.

Every major free/open license has a unique SPDX identifier which allows communicating the license choice unequivocally. We will be using that to indicate the license for every file in your project folder, along with the year of publication and the copyright holder. To do this, we add a comment to the beginning of every file and include the two tags SPDX-FileCopyrightText and SPDX-License-Identifier. How this works depends on the file type, as the syntax for a comment varies.

For example, the file Manuscript.qmd was provided to you under CC0 1.0. You can indicate that by adding the following comment to the beginning of the file:

Manuscript.qmd

<!--

SPDX-FileCopyrightText: 2024 Christoph Scheffel

SPDX-FileCopyrightText: 2024 Josephine Zerna

SPDX-License-Identifier: CC0-1.0

-->You need to use <!-- and --> to start and end the comment because this is the convention that starts comment lines in Quarto files. Alternatively, you can use the reuse tool to add these information for you. After installing it with…

Terminal

pipx install reuse…you can add the copyright information using the following command – the current year will be added automatically. In many cases, the reuse tool will figure out the appropriate comment style for you. If this is not the case, as currently with Quarto files, you can tell it directly which comment style to use (html in this case):

Terminal

reuse annotate --copyright="Josephine Zerna" --copyright="Christoph Scheffel" --license="CC0-1.0" --style=html Manuscript.qmdAs you edited the file throughout this tutorial, you may also add yourself.9

Terminal

reuse annotate --copyright="<YOUR NAME>" --license="CC0-1.0" --style=html Manuscript.qmdSometimes, there are file types which do not allow for adding the license information inside them, such as PDF and CSV files. For these, a corresponding .license file can be created. Try the following command which indicates that the data were published under CC0 1.0:

Terminal

reuse annotate --copyright="Allison Horst" --copyright="Alison Hill" --copyright="Kristen Gorman" --license="CC0-1.0" data.csvYou will notice that this creates another file called data.csv.license containing the relevant information:

data.csv.license

SPDX-FileCopyrightText: 2024 Allison Horst

SPDX-FileCopyrightText: 2024 Alison Hill

SPDX-FileCopyrightText: 2024 Kristen Gorman

SPDX-License-Identifier: CC0-1.0If you want to indicate the license for all files in a particular folder, you can create a file called REUSE.toml and add an [[annotations]] table for them:

REUSE.toml

version = 1

# apaquarto extension from https://github.com/wjschne/apaquarto

[[annotations]]

path = "_extensions/wjschne/apaquarto/*"

SPDX-FileCopyrightText = "2024 William Joel Schneider <w.joel.schneider@gmail.com>"

SPDX-License-Identifier = "CC0-1.0"Finally, there may be some minor files which are build artifacts. You can either add them to your .gitignore file or use CC0 1.0 with a copyright tag such as SPDX-FileCopyrightText: NONE to assert that there is no copyright holder. For more information, also discussing other corner cases, you can read their Frequently Asked Questions.

Once you are done, you can download the texts of all indicated licenses using…

Terminal

reuse download --all…and verify that you did not miss a file by running…

Terminal

reuse lintThe manuscript and the bibliography file you downloaded for this tutorial are made available to you under CC0 1.0 as is all code in this tutorial (e.g., for the data analysis). Therefore, you can apply any license to your modified version. Please apply the license of your choice now, using any of the methods mentioned above (except the README, which we will cover later).

LICENSE.txt (Solution)

In the following example, the edited manuscript files have been multi-licensed under AGPLv3 (or later) or (at the option of the reuser) under CC BY-SA 4.0, while the bibliography is made available under CC0 1.0.

LICENSE.txt

The Quarto documents stored in "Manuscript.qmd", "Manuscript.tex", and "Manuscript.pdf" by Josephine Zerna, Christoph Scheffel, and <YOUR NAME> are available under AGPLv3 (or later) <https://www.gnu.org/licenses/agpl-3.0.html> or (at your option) under CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/>.

The bibliography (stored in "Bibliography.bib") by Florian Kohrt and <YOUR NAME> is available under CC0 1.0 <https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/>.As the AGPLv3 requires reusers adding the full license text, we recommend to also copy it to the project folder (if not already in there).

After choosing a license, commit your changes:

Terminal

git status

git add .

git commit -m "Add license"Additional Figures

flowchart TB

start("We want to choose a<br>license for software,<br>writing, image, audio,<br>or video.") --"We adapted a work by<br>others shared under a<br>free/open license."--> use_existing_license["<em>Use its license</em>"]

start --"We created the work<br>entirely by ourselves."--> regulation("Other regulation<br>(by community or funder)<br>concerning license?")

regulation --"Exists"--> follow_existing_norms["<em>Follow that</em>"]

regulation --"Does not<br>exist"--> type("Work type?")

type --"Software"--> code_sa("Attribution?<br>Indicate license?<br>Add license text?<br>State changes?<br>Disclose code?<br>Copyleft?")

type --"Writing, image, audio, video"--> nocode_cc("Attribution?<br>Indicate license?<br>State changes?<br>Anti-DRM?<br>Copyleft?")

code_sa --"Attribution &<br>Add license text &<br>State changes"--> apache["Apache 2.0"]

code_sa --"Attribution &<br>Indicate license &<br>Disclose code &<br>Weak copyleft"--> mpl["MPL 2.0"]

code_sa --"Attribution &<br>Add license text &<br>State changes &<br>Disclose code &<br>Strong copyleft"--> agpl["AGPLv3"]

nocode_cc --"Neither"--> cc0["CC0 1.0"]

nocode_cc --"Attribution &<br>Indicate license &<br>State changes &<br>Anti-DRM"--> cc_by["CC BY 4.0"]

nocode_cc --"Attribution &<br>Indicate license &<br>State changes &<br>Anti-DRM &<br>Copyleft"--> cc_by_sa["CC BY-SA 4.0"]

click apache href "https://choosealicense.com/licenses/apache-2.0/"

click mpl href "https://choosealicense.com/licenses/mpl-2.0/"

click agpl href "https://choosealicense.com/licenses/agpl-3.0/"

click cc0 href "https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/"

click cc_by href "https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/"

click cc_by_sa href "https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/"

Note. DRM = digital rights management

flowchart TB

start("We want to choose a<br>license for data.") --"We adapted a database by<br>others shared under a<br>free/open license."--> use_existing_license_db["<em>Use its license(s)<br>for content and database</em>"]

start --"We created a database<br>entirely by ourselves."--> regulation("Other regulation<br>(by community or funder)<br>concerning license?")

regulation --"Exists"--> follow_existing_norms["<em>Follow that</em>"]

regulation --"Does not<br>exist"--> existing_license_content("Adapting content<br> by others?")

subgraph content["<strong>License for content</strong>"]

existing_license_content --"No, we created the content<br>entirely by ourselves."--> facts("Entries are facts<br>(like measurements<br>or metadata)?")

existing_license_content --"Yes, it was<br>shared under a<br>free/open license."--> use_existing_license_content["<em>Use that license</em>"]

facts --"Yes"--> cc0_content_metadata["CC0 1.0"]

facts --"No"--> choose_license["<em>Consult flowchart for<br>software, writing,<br>image, audio, and video</em>"]

end

subgraph database["<strong>License for database</strong>"]

choose_license --> switch_license["<em>Depending on<br>content license</em>"]

use_existing_license_content --> switch_license

cc0_content_metadata --> cc0_db["CC0 1.0"]

switch_license --"CC0 or<br>non-CC license"--> sa("Attribution?<br>Indicate license?<br>Anti-DRM?<br>Copyleft?")

switch_license --"CC BY or<br>CC BY-SA"--> same["<em>Same license for DB</em>"]

sa --"Neither"--> cc0_db

sa --"Attribution &<br>Indicate license &<br>Anti-DRM &<br>Copyleft"--> odbl["ODbL 1.0"]

%% the following link is only added to have terminal nodes on the same level

sa ~~~ same

end

click cc0_content_metadata href "https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/"

click cc0_db href "https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/"

click odbl href "https://opendatacommons.org/licenses/odbl/summary/"

Note. DRM = digital rights management

References

Footnotes

Copyleft licenses even require you to choose the same or a compatible license.↩︎

Of course, this is only a heuristic and there might be good reasons to deviate from community norms.↩︎

because (among other reasons) they explicitly disclaim any conveyance of patent rights (see Creative Commons, 2024)↩︎

because they often require to display the full text of the license (see Wikipedia contributors, 2025)↩︎

that is, a license for writing, image, audio, and video↩︎

The exception is when the software is part of the output (see Free Software Foundation, 2024).↩︎

a variant of the AGPLv3 that does not cover software running as a service↩︎

in Germany: Verwertungsgesellschaft↩︎

For licenses that require that modifications are indicated, this is an easy way to comply with them. Also, you do not need to provide your real name.↩︎