Understanding {renv}

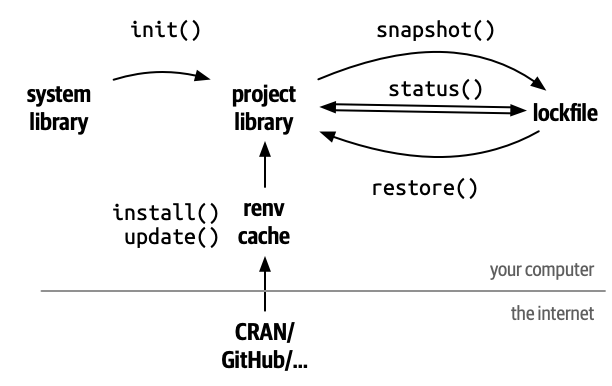

The previous page introduced the main functions needed for using {renv} in a project, and showed short example snippets of how to use them. This page will provide a more detailed explanation of the functions renv::init(), renv::status(), and renv::snapshot(), and will provide a more detailed example of how to use them in a project. Later chapters will cover the system library/renv cache and restoring a project from a lockfile.

Initiating {renv}

As you might have noted from the videos in the previous sections, initiating a project with {renv} will cause the following changes to your project:

- Creation of a lockfile,

renv.lock, which records the version of R in use, the default download repository, and the packages used in the project. - Creation of a

renvfolder which contains the projectlibrary1, a settings file, a.gitignorefile and a staging area for package installation - Addition of the line

source("renv/activate.R")to your.Rprofile. This file is automatically run anytime a project session is started by e.g. opening the*.Rprojfile. This line ensures that the project library is used in the session, not the global library.

Adding renv to a project also updates the .Rbuildignore to include the renv folder and the renv.lock file. This is only relevant if you’re building an R package.

You should rarely, if ever, need to interact directly with any of the files or folders created by {renv}. The lockfile is the most important file, as it records the packages used in the project and their versions, and should be maintained with calls to functions from the {renv} package such as snapshot().

{renv} with Git & GitHub

Ideally, you will use {renv} in projects that are under version control with Git (or another version control system) because “one of the reasons to use renv is to make it easier to share your code in such a way that everyone gets exactly the same package versions as you.” In order to do this successfully, note the advice on collaborating with {renv} in the official documentation.

You’ll then need to commit

renv.lock,.Rprofile,renv/settings.jsonandrenv/activate.Rto version control, ensuring that others can recreate your project environment. If you’re using git, this is particularly simple because renv will create a .gitignore for you, and you can just commit all suggested files.

The above also assumes that you are working within an RProject (*.Rproj) structure.

Initiation Example

Initiating {renv} in a project should print the following to the console:

renv::init()

#> The following package(s) will be updated in the lockfile:

#>

#> # CRAN -----------------------------------------------------------------------

#> - renv [* -> 1.0.7]

#>

#> The version of R recorded in the lockfile will be updated:

#> - R [* -> 4.4.0]

#>

#> - Lockfile written to "~/Desktop/temporary".Notably, one can see that the version of R (4.4.0) and the renv package (1.0.7) are recorded in the lockfile immediately. If you are initiating renv in an already existing project, the lockfile should also identify the other packages and package versions in use.

For reference, the directory structure should look similar to the one below, particularly the presence of the renv directory and the renv.lock file.

# the function used in the following example, `dir_tree()`, is from the {fs} package and is used

# to display the directory structure of the project. That is, it will list the files and

# directories in the directory where you are currently working.

fs::dir_tree(recurse = 2)

#> .

#> ├── renv

#> │ ├── activate.R

#> │ ├── library

#> │ │ └── macos

#> │ ├── settings.json

#> │ └── staging

#> ├── renv.lock

#> └── temp.RprojPackage Detection

{renv} is designed to detect the packages you are using in your project. Before discussing the details of how {renv} detects packages, it is important to understand dependencies in some detail.

Dependencies Revisited

At the first degree, you depend on packages to perform your analysis or for your project, and you likely have included these packages in your project via calls to library(), require(), or namespaced calls e.g. package::function(). It is quite obvious that these packages are dependencies of your project, and thus need to be included in the renv.lock file.

However, how does {renv} detect what packages are being used in the project? The renv:dependencies() function! This function works by searching all R-related files (e.g. .R, .Rmd, .qmd) for calls to packages. It is important to note that this function only detects packages that are actually used and properly declared in the project. Packages that have only been used interactively will not be detected as dependencies because they are not saved or used in any of the project files.

You will likely never need to use renv::dependencies() directly, but being aware of what it does can be massively beneficial in troubleshooting issues in the future. More importantly, this function underlies the renv:status() and renv::snapshot() functions which are essential for using {renv}. Before discussing these functions in detail, let’s take a look at the dependencies of dependencies.

Dependency Trees

As mentioned in the Dependencies Overview, project dependencies can have their own dependencies. For example, you might have noticed that when installing 1 new package, R asks you if you want to install additional packages. These additional packages are dependencies of the package you are installing, and cumulatively they create a “dependency tree.” To get a visual representation of this, consider the following example displaying the recursive dependency tree for the {dplyr} package.

pak::pkg_deps_tree("dplyr", dependencies = "hard")

#> ℹ Loading metadata database

#> ✔ Loading metadata database ... done

#>

#> dplyr 1.1.4 ✨🔧 ⬇ (1.60 MB)

#> ├─cli 3.6.3 ✨🔧 ⬇ (1.39 MB)

#> ├─generics 0.1.3 ✨ ⬇ (81.91 kB)

#> ├─glue 1.7.0 ✨🔧 ⬇ (159.50 kB)

#> ├─lifecycle 1.0.4 ✨ ⬇ (124.78 kB)

#> │ ├─cli

#> │ ├─glue

#> │ └─rlang 1.1.4 ✨🔧 ⬇ (1.89 MB)

#> ├─magrittr 2.0.3 ✨🔧 ⬇ (233.52 kB)

#> ├─pillar 1.9.0 ✨ ⬇ (652.06 kB)

#> │ ├─cli

#> │ ├─fansi 1.0.6 ✨🔧 ⬇ (383.06 kB)

#> │ ├─glue

#> │ ├─lifecycle

#> │ ├─rlang

#> │ ├─utf8 1.2.4 ✨🔧 ⬇ (206.91 kB)

#> │ └─vctrs 0.6.5 ✨🔧 ⬇ (1.89 MB)

#> │ ├─cli

#> │ ├─glue

#> │ ├─lifecycle

#> │ └─rlang

#> ├─R6 2.5.1 ✨ ⬇ (83.20 kB)

#> ├─rlang

#> ├─tibble 3.2.1 ✨🔧 ⬇ (688.89 kB)

#> │ ├─fansi

#> │ ├─lifecycle

#> │ ├─magrittr

#> │ ├─pillar

#> │ ├─pkgconfig 2.0.3 ✨ ⬇ (18.45 kB)

#> │ ├─rlang

#> │ └─vctrs

#> ├─tidyselect 1.2.1 ✨🔧 ⬇ (224.68 kB)

#> │ ├─cli

#> │ ├─glue

#> │ ├─lifecycle

#> │ ├─rlang

#> │ ├─vctrs

#> │ └─withr 3.0.0 ✨ ⬇ (242.00 kB)

#> └─vctrs

#>

#> Key: ✨ new | ⬇ download | 🔧 compileThis tree shows the dependencies of the dplyr package at the top level, and the dependencies of those dependencies nested below each package. The tree is recursive, meaning that it will continue to show dependencies of dependencies until it reaches the end of the dependency chain. This is a simplified example, but it is important to understand that the dependencies of dependencies can be quite complex and can lead to a large number of packages being installed in your project. Above all, you should note that all of the packages on this dependency tree need to be recorded in the renv.lock file to ensure that your project is reproducible.

You might have noticed the argument dependencies = "hard" in the function call. The dependencies argument is used to specify the kinds of dependencies to install. However, the discussion about dependencies so far has implied that another package is either a dependency or not, and you might now be asking yourself: are there different kinds of dependencies? Yes, there are! To be more specific, there are different levels of dependencies, discussed below.

Dependency Levels

Generally-speaking, there are two levels of dependencies in R: hard and soft. Hard dependencies are those that are absolutely required for the software to function, while soft dependencies are those that are not required but can improve the package or provide some optional functionality. In the context of R, the following are the dependency levels:

- Hard Dependencies

- Imports

- Depends

- LinkingTo

- Soft Dependencies

- Suggests

- Enhances

The exact differences between the sub-levels of dependencies are not important for the purposes of this course, and, in most cases, the details of dependency levels are obscure and irrelevant. You will be able to successfully use R and {renv} without knowing the difference between hard and soft dependencies 99% of the time especially because most packages you download will only have Hard dependencies.

However, it is still worthwhile to be aware that these these differences exist when using automated package managers as they will default to capturing just the Hard dependencies, but you might encounter scenarios where you mistakenly expect the snapshot to include the Soft dependencies. In such cases, you might need to explicitly renv::record() the dependency into the renv.lock file. Examples of this scenario will be revisited in the exercises.

Status and Snapshot

With a basic understanding of dependencies, we can now discuss the functions renv::status() and renv::snapshot() in more detail. These functions are the backbone of {renv} and are essential for maintaining the renv.lock file.

Status

The renv::status() function checks the “status” of the project, and will return a message indicating whether the project is in a consistent state. A consistent state means that the packages declared in the lockfile match the packages actually used in the project, and that the versions of the packages declared in the lockfile match the versions of the packages discovered in the project library. For example, if you have a package declared in the lockfile but it is not actually used in the project, the project is not in a consistent state. A project that is consistent should produce the following output when renv::status() is run:

renv::status()

#> No issues found -- the project is in a consistent state.However, if there are issues with the project, the output will indicate what the issues are. For example, if a package is used in the project but not declared in the lockfile, the output will look like this:

renv::status()

#> The following package(s) are in an inconsistent state:

#>

#> package installed recorded used

#> boot y n y

#> cli y n y

#> dplyr y n y

#> fansi y n y

#> generics y n y

#> glue y n y

#> lattice y n y

#> lifecycle y n y

#> lme4 y n y

#> magrittr y n y

#> MASS y n y

#> Matrix y n y

#> minqa y n y

#> nlme y n y

#> nloptr y n y

#> pillar y n y

#> pkgconfig y n y

#> R6 y n y

#> Rcpp y n y

#> RcppEigen y n y

#> rlang y n y

#> tibble y n y

#> tidyselect y n y

#> utf8 y n y

#> vctrs y n y

#> withr y n y

#>

#> See ?renv::status() for advice on resolving these issues.The key to interpreting this output is to note the installed, recorded, and used columns. The installed column indicates whether the package is installed in the project library, the recorded column indicates whether the package is declared in the lockfile, and the used column indicates whether the package is actually used in the project. In this example, the packages are installed and used in the project, but are not declared in the lockfile. This is an inconsistent state, and the issues should be resolved by running renv::snapshot().

Snapshot

The renv::snapshot() function is used to update the lockfile with the packages used in the project. As previously discussed, this function will search all R-related files in the project for calls to library(), require(), and namespaced calls e.g. package::function(), and will update the lockfile with the packages used in the project. If the lockfile is already up to date, the function will return the following message:

renv::snapshot()

#> - The lockfile is already up to date.If the lockfile is not up to date, the function will return a message indicating the packages that will be updated in the lockfile. For example, if you have added a new package to the project, the output will look like this:

renv::snapshot()

#> The following package(s) will be updated in the lockfile:

#>

#> # CRAN -----------------------------------------------------------------------

#> - boot [* -> 1.3-30]

#> - cli [* -> 3.6.3]

#> - dplyr [* -> 1.1.4]

#> - fansi [* -> 1.0.6]

#> - generics [* -> 0.1.3]

#> - glue [* -> 1.7.0]

#> - lattice [* -> 0.22-6]

#> - lifecycle [* -> 1.0.4]

#> - lme4 [* -> 1.1-35.5]

#> - magrittr [* -> 2.0.3]

#> - MASS [* -> 7.3-60.2]

#> - Matrix [* -> 1.7-0]

#> - minqa [* -> 1.2.7]

#> - nlme [* -> 3.1-164]

#> - nloptr [* -> 2.1.1]

#> - pillar [* -> 1.9.0]

#> - pkgconfig [* -> 2.0.3]

#> - R6 [* -> 2.5.1]

#> - Rcpp [* -> 1.0.13]

#> - RcppEigen [* -> 0.3.4.0.0]

#> - rlang [* -> 1.1.4]

#> - tibble [* -> 3.2.1]

#> - tidyselect [* -> 1.2.1]

#> - utf8 [* -> 1.2.4]

#> - vctrs [* -> 0.6.5]

#> - withr [* -> 3.0.0]

#>

#> - Lockfile written to "~/Desktop/temp/renv.lock".Packages not already installed in the project can be recognized by the [* -> version] notation. The [*] indicates that the package is not installed in the project library, and the version indicates the version of the package that will be installed. The lockfile is then written to the project directory, and the project should now in a consistent state.

Footnotes

Strictly speaking, the directory

renv/librarycontains symlinks or symbolic links to packages in the renv library, which is a cache of the packages used in the project. This “cached” library is a shared library, meaning that if you have multiple projects using the same version of the package, the package is only stored once on your computer. This is a huge space saver, especially if you have many projects using the same package. More on this in the Caching chapter.↩︎