Citation Politics: what is it and why should we care?

11/03/2026

Licence

This current work by Sara Lil Middleton, Sarah von Grebmer zu Wolfsthurn and Flavio Azevedo is licensed under a CC-BY-SA 4.0 Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International SA License. It permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you must distribute your contributions under the same license as the original.

Contribution statement

Creator: Middleton, Sara Lil (![]() 0000-0001-5307-8029)

0000-0001-5307-8029)

Reviewer: Von Grebmer zu Wolfsthurn, Sarah (![]() 0000-0002-6413-3895)

0000-0002-6413-3895)

Consultant: Azevedo, Flavio (![]() 0000-0001-9000-8513)

0000-0001-9000-8513)

Prerequisites

Important

Before completing this submodule, please carefully read about the necessary prerequisites.

- You will need access to a piece of your own work (a report, essay, journal article, blogpost, presentation) containing a bibliography with 10 or more references, preferably in .bib or .txt file format (this is needed for the GBAT assessment).

Questions from the previous submodule?

Your citation politics journey

From: “I am not sure what citation politics is or why it is important”

To: “I feel empowered to adopt more contentious citation practices”

Before we start: Results of survey!

1. How familiar are you with the concept of citational politics?

Scale 1 to 5: 1 = never heard of it, 5 = extensive knowledge.

Never heard of it

Basic knowledge, but cannot describe in detail

Some knowledge and can discuss

Some knowledge, can discuss and relate to with other issues

Extensive knowledge

2. How would you rate your confidence to carry out an audit of your citational practices on your work?

Scale 1 to 5: 1 = Not confident at all , 5 = Completely confident)

Not confident at all

Slightly confident

Somewhat confident

Very confident

Completely confident

3. List three adjectives that you expect or hope to feel at the end of the class

Discussion of survey results

What do we see in the results?

Aim and overview

Aim: Examine the concept of citational politics, its links to knowledge production and dissemination and learn to use some tools and practices for more conscientious citations.

There are five sections to this submodule:

Section 1: Introduction to citations

Section 2: Citation politics: the mechanisms and consequence of citational inequities

Section 3: When should we think about citations?

Section 4: Conducting a citational self-audit

Section 5: Wrap up and what can we do to move towards citational equity?

Section 1: Learning goals and overview

Section 1 is all about learning the key terms and definitions and to get you thinking about the what and the why of citations.

Activity: “Think-pair-share” discussions

After completing Section 1 you should be able to:

Recognize the social and political context of citations

Explain why citational practices are not neutral

Section 2: Learning goals and overview

In Section 2 we will examine the mechanisms and consequences of citational inequities.

Activity: Pass the discussion (ball)

After completing Section 2 you should be able to:

Identify and describe some of the mechanisms and effects of citational inequities

Give examples of how consequences of citational disparities impact individuals and the research ecosystem

Section 3: Learning goals and overview

Section 3 looks at which stages in our work we should think about citations.

Activity: Small group discussions

After completing Section 3 you should be able to:

Recognize the main stages of research from ideas to producing a report, essay, journal article

Classify which citational tools and practices can be used during each of the four major research stages: planning, project, paper and publication.

Section 4: Learning goals and overview

Section 4 is all about putting to practice what you have learned and conducting your own citational self-audit!

Activity: Citational self-audit for gender diversity

After completing Section 4 you should be able to:

- Assess the gender diversity of a bibliography from your own work.

Section 5: Learning goals and overview

Finally, in Section 5 we will recap the previous sections

Activity: End of submodule quiz (open book)

After completing Section 5 you should be able to:

- Summarize the key terms relating to citational politics (citations, citational politics, citational cliques)

- Explain how to conduct a self-audit of your citation practices

Section 1: Introduction to citations

Warm up question to get us started!

What are citations, and why do we cite?

- Think about answer on your own

- Discuss answer with neighbor and write out a joint answer

- We will share our answers in class

What are citations?

Definition

A reference to an information source, where the original author is given credit.

Citations map out the lineage of ideas upon which scholarship is built and informs what knowledge we value and whose knowledge we platform.

Citations are a key currency in academia where more citations equal more prestige (e.g. H-Index) (Sauvé et al., 2025).

For example, this definition cites work by Sauvé and colleagues from 2025 where the full reference will appear in the bibliography at the end.

Citations as a knowledge map

Citations play an important role in tracing the conceptual origins and evolution of ideas during literature searches (Ghosal & Singh, 2021)

Citations are used to provide background context to piece of work, particularly in introductory sections.

Some papers cite other works with closely tied research themes, build on these ideas and push the boundaries of knowledge in new directions.

Did you know?

The study of citations and other bibliographic data is known as bibliometrics (Donthu et al., 2021)

Analyzing citation practices

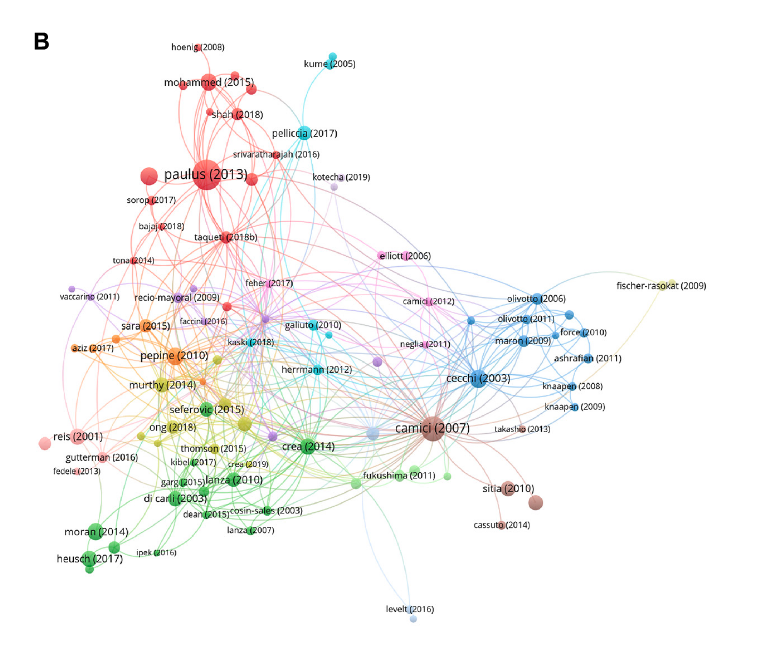

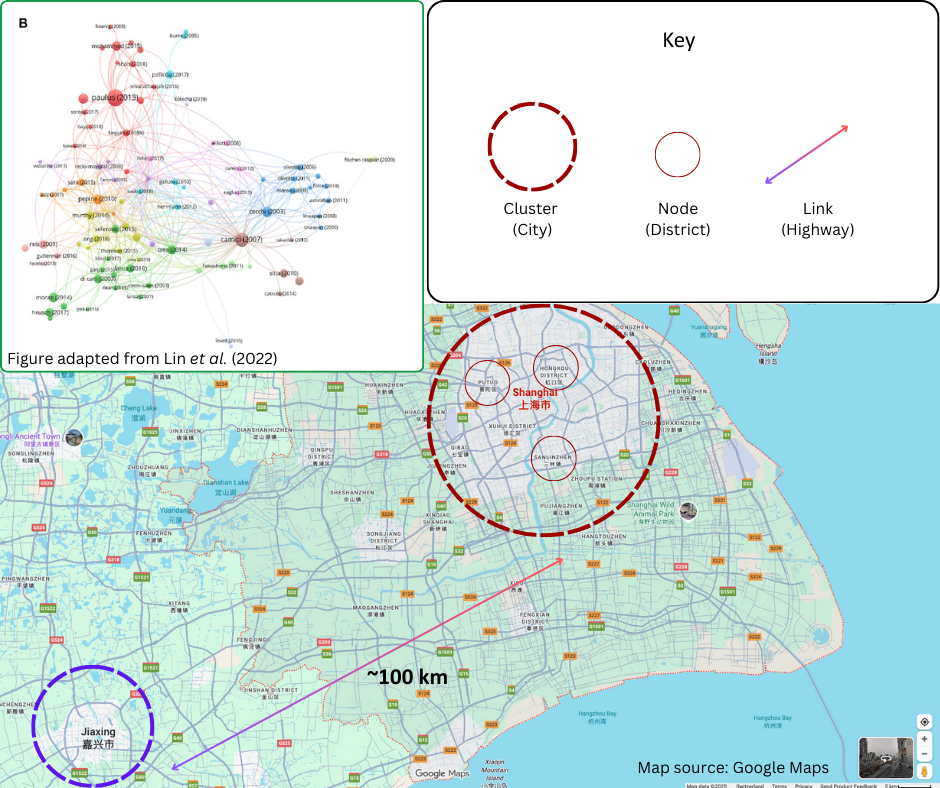

Bibliometric analyses can reveal patterns in citation practices (e.g. most cited papers or scholars and citational clusters)

Figure adapted from Lin et al. (2022)

Components of citation maps

A node is like a busy urban center with links to other nodes via highways, where several nodes can form clusters

Analogy: the Putuo, Hongkou, Sanlinzhen districts (nodes) have closer links forming city of Shanghai (cluster) compared to districts in Jiaxing >100 km away

Citation metrics as an evaluation tool

- Citation metrics (e.g. H-Index) are an evaluation tool used to make important decisions like career progression, funding allocations and conference speaker invites (Gupta et al., 2025).

Definition

Hirsch’s Index (H-Index) is an author-level metric used to assess productivity and impact of publications (Hirsch, 2005).

It is calculated by the number of publications with citation number ≥ h (e.g. if a scholar has a total of 10 publications and 7 of those each have at least 7 citations, then their H-Index = 7)

- Scholars with higher H-Indices are often evaluated more highly, but there are inherit biases with this…

Biases in citation metrics

The number of citations is not only a measure of quality and productivity, as being highly cited relies on opportunities to publish a lot which links to:

- Academic factors: career stage, academic discipline, institutional affiliation, mentoring, support networks.

- Social, cultural and economic factors: gender, race, ethnicity, nationality, socio-economic status, disability.

Where these factors interact and compound resulting in disparities in citation rates.

Citations as a politic

- Citations are more than a technical formality

- Citation practices are not neutral as they reflect an academic system that is unequal

- There is lots of evidence to show citational biases towards Anglophone racialized white men across disciplines (Sauvé et al., 2025).

Definition

- Citation politics reflects choices scholars make in who they cite and who they overlook in their work.

- There are inherent biases and systemic inequalities that result in epistemic hierarchies – that is the recognition and legitimization of dominant world views at the exclusion of others knowledge systems (Sauvé et al., 2025).

Section 2: Citation politics: the mechanisms and consequences of citational inequities

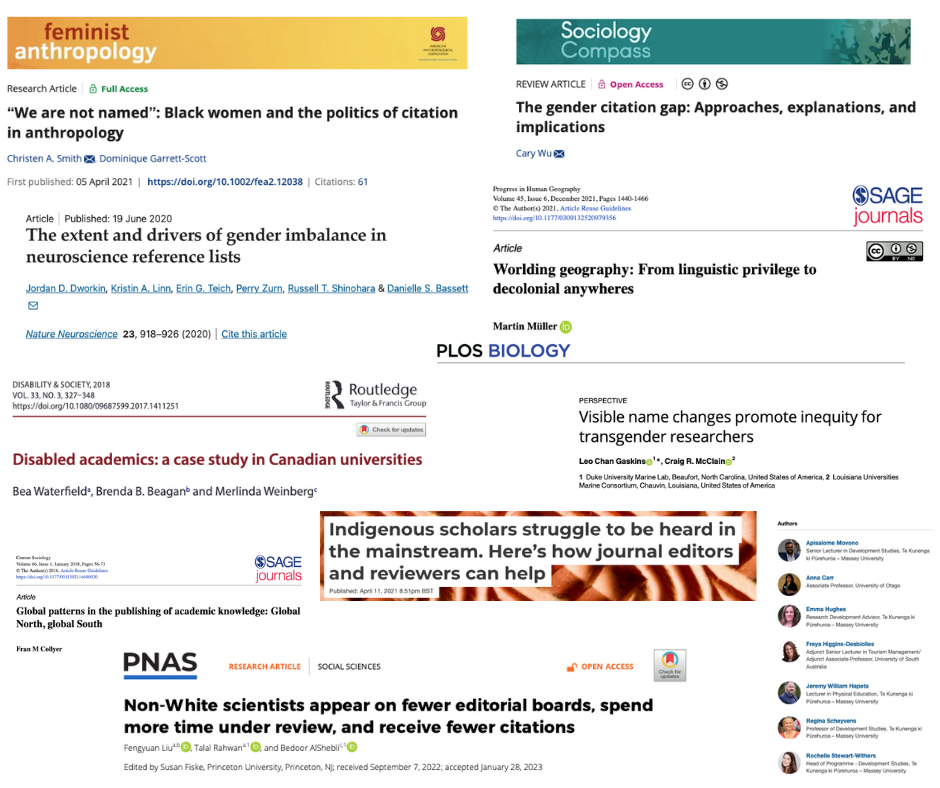

Citational inequity patterns (I)

Citational disparities across marginalized groups

Citational inequity patterns (II)

There is currently more research on gender bias in citation patterns than for other marginalized identities (e.g. Matilda effect)

This does not mean other marginalized scholars are not also experiencing a lack of citation!

Identities are multifaceted, where scholars with more marginalized identities face compounding barriers

Matilda effect

The women’s share of highly cited researchers (HCRs) increased 0.9% from 13.1% in 2014 to 14.0% in 2021.

To reach parity with men, women’s share of HCRs would need to increase 100% in health and social sciences and 500% in engineering, chemistry and computer science (Meho, 2022).

This is an example of the Matilda effect - the systematic undervaluing of women’s contributions to research (Rossiter, 1993).

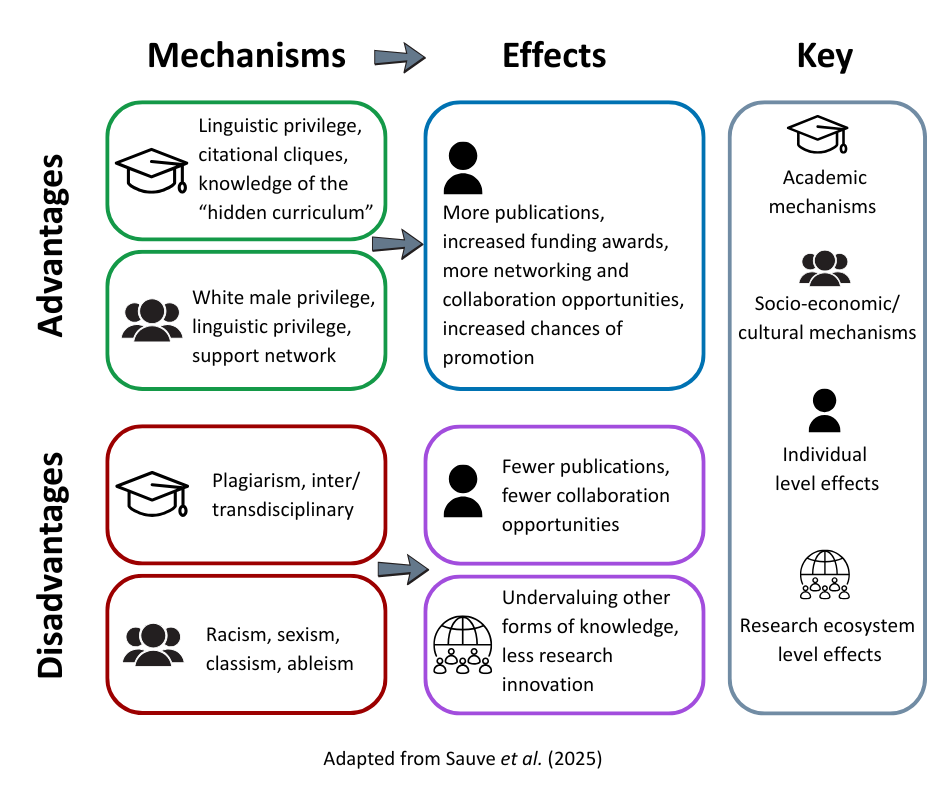

Mechanisms of citational inequities

Socio-economic and cultural mechanisms: operate at systemic, structural and inter-personal levels relating to systems in our society such economic, political and health (e.g. racism and sexism)

Academic mechanisms: relate to policies, practices, and norms occurring within the academic system (e.g., citational cliques)

Mechanism levels

Systemic emphasizes whole systems. Structural refers to the embedded policies/practices that provide scaffolding of systems. Inter-personal is about interactions and behaviors between people and teams (Braveman et al., 2022). Mechanism levels can overlap!

Academic mechanisms: Plagiarism, citational cliques, “hidden curriculum”

Definitions

Plagiarism: To present work ideas from another author or work as one’s own without crediting the source (Park, 2003).

Citational cliques: A citational practice that describes how networks of authors or journal editors can game the system by excessively citing each other to increase their citational metrics (H-Index for authors, Impact Factors for journals) (Franck, 1999; Kojaku et al., 2021).

Hidden Curriculum: A highly contextual set of social norms, practices and values not explicitly taught as part of official teaching. The impact of the hidden curriculum disproportionately felt by marginalized groups (Jackson, 1990) (e.g. many scholarly awards allow self-nomination, which might not be immediately apparent).

Academic mechanisms: Linguistic privilege and inter/transdisciplinarity

- Linguistic privilege and inter/transdisciplinarity are two contributors to citational disparities that are often overlooked.

Definitions

Linguistic privilege: The operating language of academia is English. Native (or near native fluent) speakers hold more advantages than non-native speakers in publishing, peer review process, citation rates and conferences (Müller, 2021).

Inter/transdisciplinarity: Scholars whose research covers multiple domains, especially in biological and health sciences, can be disadvantaged during the publishing process and are often evaluated the same as scholars working within a single domain (Levitt & Thelwall, 2008).

Mechanisms and effects of citational inequities

The Matthew effect

The impact of biases and systemic inequalities in citation practices are cumulative:

- Scholars with more advantages (e.g. white male privilege, citational cliques) are more likely to publish, be cited, receive academic recognition and promotion and vice versa for scholars experiencing barriers (e.g. sexism, racism, plagiarism).

Definition

The Matthew Effect is a phenomenon coined by Merton (1968) after the ‘rich get richer; poor get poorer’ saying in the Gospel of Matthew. It describes the self-reinforcing accumulation of recognition and prestige within the academic system.

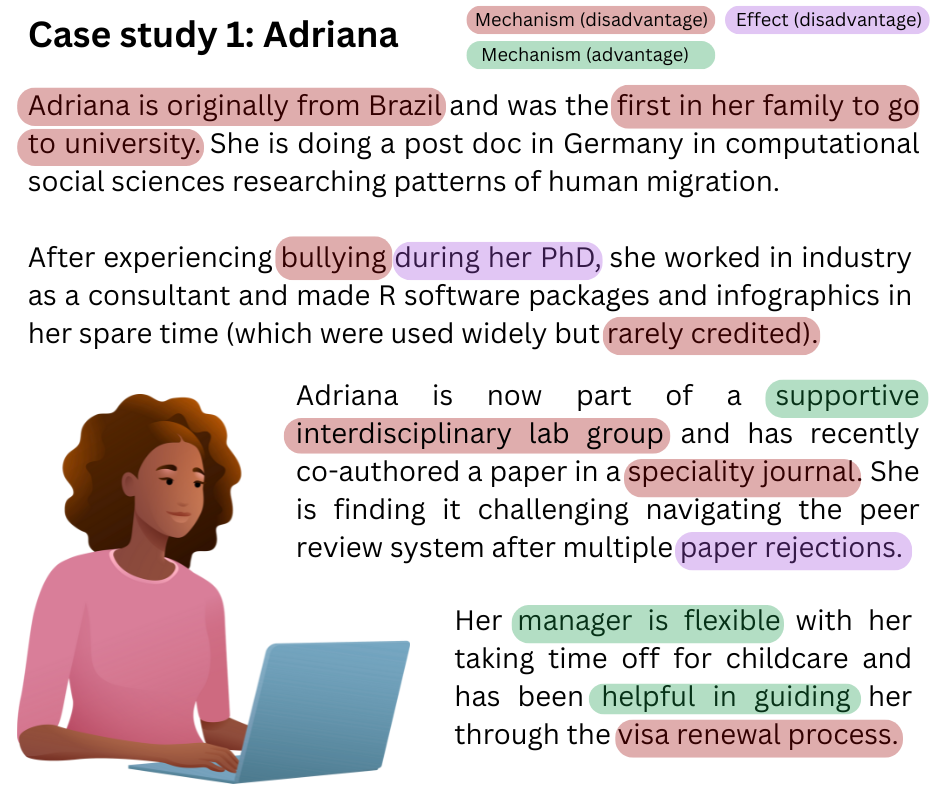

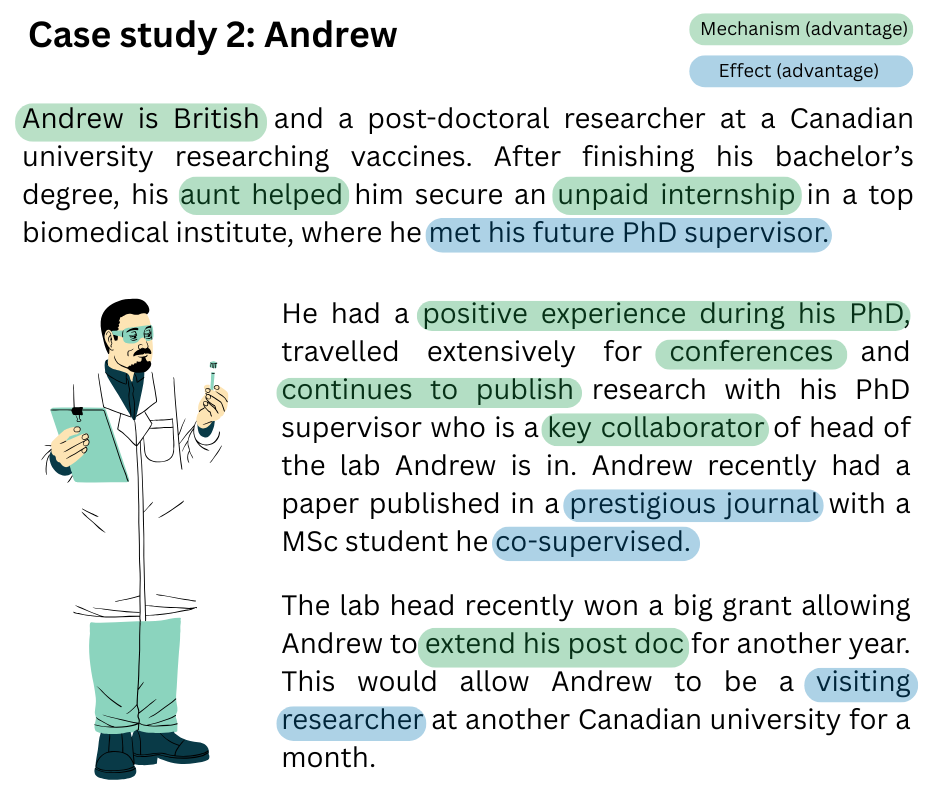

Group discussion exercise

Pass the discussion (ball)

- Read both case studies

- Think about mechanisms and effects

- Discuss the case studies as a group

Questions to think about

- What are some mechanisms you can identify?

- Can you distinguish between social vs academic mechanisms?

- What are the main differences in consequences that exist between these two case studies?

- Can you describe what are some of the negative effects to the research ecosystem?

Case study 1: Adriana

Case study 2: Andrew

Comparing case studies

Questions to think about

- What are some mechanisms you can identify?

- Can you distinguish between social vs academic mechanisms?

- What are the main differences in consequences that exist between these two case studies?

- Can you describe what are some of the negative effects to the research ecosystem?

Case study clues

Tip

Some mechanisms are not always explicit (e.g. Adriana is likely to be less aware of the hidden curriculum as she is a first-generation student).

Summary of Sections 1 and 2

- Citations are more than referencing a source of information

- Citations practices (e.g. citational cliques) can be mapped using bibliometric analyses

- Extensive documented evidence to show citational biases and systemic inequalities, particularly against women (e.g. Matilda effect)

- Citations are key currency in academia influencing hiring, funding and promotion decisions

Take home message

Academic recognition is regulated via the choices we make in who we cite and who we do not.

Break time!

Section 3: When should we think about citations?

The four stages to research

- Planning: project conceptualization, funding acquizition

- Project: literature search, data collection

- Paper: writing up research findings, submitting to a journal

- Publication: peer review process, publishing research

Note

In arts and humanities, outputs may not always be in a written format (e.g. art pieces, audio or video) or researchers dealing with ancient texts contain fewer citations than in STEM subjects (Colavizza et al., 2023).

Self and group reflection (I)

This exercise aims to get you thinking about your own research process and when you think about citations.

- Self-reflect on question 1

- Discuss answer to question 2 in small groups (next slide)

Self-reflect

Q1: When do you typically think about citations in your work?

Self and group reflection (II)

Discuss answer to Q2 in small groups (8 minutes)

Q2: At which stage of research do you consider the most important to think about citations?

Towards more mindful citation

We typically think about citations when we come to write up our research findings (paper stage)

This often reflects how we have been taught (citations as academic bookkeeping)

Thinking and acting more broadly in our citation practices requires small incremental and sustained actions

Mindfulness beyond citations

Being mindful of our research processes extends to other practices too across the research life cycle. See our Research Cycle Handbook!

Tools and practices

Adapted from Sauvé et al. (2025)

Planning

- Citational transparency browser extension

- FORRT citational justice module

Project

- Diversify your reading

Paper

- Gray Test

- Citational diversity codebook

- Citing R packages

- Annotated reference list

Publication

- FORRT Academic Wheel of Privilege

Section 4: Conducting a citational self-audit

What does it mean to do a self-audit?

Self-auditing is an important part of evaluating your skill sets and ways of working

You are likely to do a self-audit multiple times in your educational or academic career (e.g. during a performance review, training needs analysis or appraisal)

Self-audits are a key part of professional or business development

Definition

Self-auditing is a process of self- reflection and evaluation of one’s knowledge, skills or practices and taking accountability by implementing plans to improve standards/performance (Middleton et al., 2025).

Tools to do a citational self-audit

Manually examining our reference lists is challenging due to unknown demographic markers of the authors we cite and it is time consuming

There are a number of tools that help automate this process like Gender Balance Assessment Tool (GBAT) (Sumner, 2018, 2024), genderize, GCBI-alyzer (Fulvio et al., n.d.).

Gender Balance Assessment Tool (GBAT)

GBAT is an automated web-based tool that evaluates the gender balance of a bibliography list developed by Sumner (2018) in response to the chronic under citing of women in political science

It works by identifying names from an author list, estimating the gender probability for the whole author list to produce a final percentage estimate

Caveates

GBAT uses probabilistic inference meaning it relies on algorithms to identify and predict the gender of names. It can misidentify authors’ gender (e.g. those with uncommon names, names common to both genders or identifying as non-binary, transgender or gender diverse).

Citational self-audit with GBAT

Now to practice using GBAT (10 minutes):

- Open your .bib or .txt document which has a bibliography list

- Estimate the % of women and % men in your author list

- Visit https://jlsumner.shinyapps.io/syllabustool/ and follow the instructions

- Record your final % gender balance score

- Compare your estimate with the GBAT score

- Reflect on the process: were you surprised by the result?

Trouble-shooting

- If an error occurs when uploading file, copy and paste author list into text box without bullet points

- The GBAT tool can show “disconnected from the server” when left idle. To reactivate, refresh the page.

Reporting citational diversity scores

- You can use the scores generated from GBAT or other tools to write part of a citation diversity statement

- These statements are used to raise awareness and mitigate citational inequities

- Citation diversity statements appear at the start of reference lists of articles and are increasingly encouraged by journals

Citation diversity statements

Citation diversity statements have four parts: 1) the issues and importance of citational diversity, 2) citation diversity scores (e.g. GBAT), 3) methods and caveats of scoring approach used, 4) a commitment to improving citational practices (Zurn et al., 2020).

Summary of sections 3 and 4

Out of the four main research stages: 1) planning, 2) project, 3) paper, 4) publication, we typically think about citations when we write up our research

Many tools and practices exist to help us be more mindful of how we cite across the research stages

Self-auditing our citation practices is an important reflective exercise to evaluate our current knowledge and skills and put in place plans to develop them further

Take home message

Citations are not just an “add on” and should be thought about regularly as we carry out our research!

Section 5: Wrap up and what can we do to move towards citational equity?

Final summary

Citation politics recognizes citations as more than academic bookkeeping. They are choices we make in whose knowledge is valued or sidelined, reflecting the inherent biases and systemic inequalities present in academia

Citation politics matters because these inequalities are unjust, leading to epistemic hierarchies that impact individual scholars livelihoods and the wider research ecosystem

We all have a role to play in addressing these inequities by doing citational self-audits and adopting tools that promote conscientious citations.

Take home message

“Do the best you can until you know better. Then when you know better, do better.” Maya Angelou

End of submodule quiz!

Q1: Citational politics is about:

Answer to Q1: Citational politics is about:

Q2: Which one of the following is an example of a mechanism typically resulting in academic advantages?

Answer to Q2: Which one of the following is an example of a mechanism typically resulting in academic advantages?

Q3: True or false, citation practices only matter when writing up my research?

Answer to Q3: True or false, citation practices only matter when writing up my research?

Q4: True of false, Part of (citational) self-auditing is about taking accountability for how we engage with the practice of citation?

Answer to Q4: True of false, Part of (citational) self-auditing is about taking accountability for how we engage with the practice of citation?

Before we end: Revisiting the survey!

1. How familiar are you with the concept of citational politics?

Scale 1 to 5: 1 = never heard of it, 5 = extensive knowledge.

2. How would you rate your confidence to carry out an audit of your citational practices on your work?

Scale 1 to 5: 1 = Not confident at all , 5 = Completely confident)

3. List three adjectives that you expect or hope to feel at the end of the class.

Advanced task: Citational justice action plan

Using the Citational Justice Toolkit by Sauvé et al. (2025):

Pick one tool or practice to commit to implementing in your work over the next X number of months.

To remain accountable, share the time frame and evaluation of implementing a citational tool/practice with someone else in class.

Advanced task: Citational justice action plan questions

To help you make your action plan, consider the questions below. You can also ask your accountability buddy these questions to help improve their plan.

Guiding questions

- Explain why you have chosen this tool/practice

- Why is it needed in your work/research context

- Explain how you will evaluate the success of your chosen citational tool/practice after X months

- Decide what action you will take in the coming 1) days, 2) weeks, 3) months/end of term.

Additional resources

Citation Politics Toolkit developed by FORRT: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HuQEmrME6uk

Related modules

This Citation Politics module relates to the following module:

Zotero

Introductory slide decks (aimed at novices): https://lmu-osc.github.io/train-the-trainer-student-track-OS/materials/OS-M3/OS-M3-S1-Zotero/OS-M3-S1-Zotero.html

Self-paced tutorial: https://lmu-osc.github.io/introduction-to-zotero/

Citation diversity statement

Citation practices are not neutral and disparities exist in whose knowledge is recognized and whose not, with women, Black, Indigenous, disabled and other marginalized groups consistently underrepresented in reference lists.

To that end, we actively sought out papers from a range of disciplines, and researchers, with a bias towards uplifting Global Majority scholars. We assessed the gender diversity of our reference list using the Gender Balance Assessment Tool (GBAT) by Sumner (2018). Names were identified from the author list, and an estimate of the gender balance was produced using proboblastic techniques, where the author list in this training module contains approximately 49.32% women and 50.68% men.

We acknowledge this method can misidentify an author’s gender especially those with uncommon names, names common to both genders or identifying as non-binary, transgender or gender diverse. We strive to continually improve on the quality and diversity of our resources we draw upon in our training materials and are open to suggestions.

Contribution Statement

Sara Lil Middleton: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization, Validation, Project Administration. Sarah von Grebmer zu Wolfsthurn: Software, Writing - Review & Editing, Validation, Project Administration. Flavio Azevedo: Resources.

References

Thanks!

See you next class :)

Additional literature for instructors

References from instructor notes:

Liboiron, M. (2023, August 8). Citational politics training module. CLEAR. https://civiclaboratory.nl/2023/08/08/citational-politics-training-module/

Active Learning Activities | Centre for Teaching Excellence. (n.d.). Uwaterloo.ca. https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/catalogs/tip-sheets/active-learning-activities

LMU Open Science Center